We have to ask about eating disorders

A glaring hole in the mental health conversation, and a few ideas to address it

This has taken me a year to write.

Mostly, because it’s such an unbelievably complicated issue… one I’m painfully aware won’t be solved with one Substack article.

But also, because it’s a personal one.

For a long time now, I’ve closely followed the Ozempic mania. I’ve followed the “thin is in” articles… the pro-ED TikTok rabbit holes… the Kardashian effect… the Taylor Swift lyrics… the "Taylor Swift lyrics are fat-phobic" backlash… the rumors, the clickbait… and obviously, especially, the legitimate cultural analysis.

I felt compelled to weigh in, because like many women (and people) who grapple with thin beauty standards and a perpetually fluctuating weight… I know there are serious emotions hiding under the surface.

I’ve sat down to write this before… crumpled many pieces of digital-equivalent paper and thrown them in the digital-equivalent bin. I’ve meditated on it, worked it out on the dance floor, reflected with time.

Most importantly, I’ve interviewed several close friends who grapple with this issue in their own ways — brave, vulnerable, thoughtful friends whom I’ll subsequently refer to as “Anonymous” and to whom I’m incredibly grateful for sharing their stories with me.

Spoiler… I still haven’t cracked it. That might take a lifetime. Maybe we never will.

But sometimes asking a question is better than having an answer… and when it comes to eating disorders, I don’t think we’re asking enough questions.

So, I’ll start there — with a few of the questions we need to ask.

First question:

How common are eating disorders?

A lot more common than we realize.

Emergency eating disorder hospitalizations rose +760% and inpatient hospitalizations +600% in the first year of the pandemic. Neither has anywhere near returned to pre-pandemic levels.

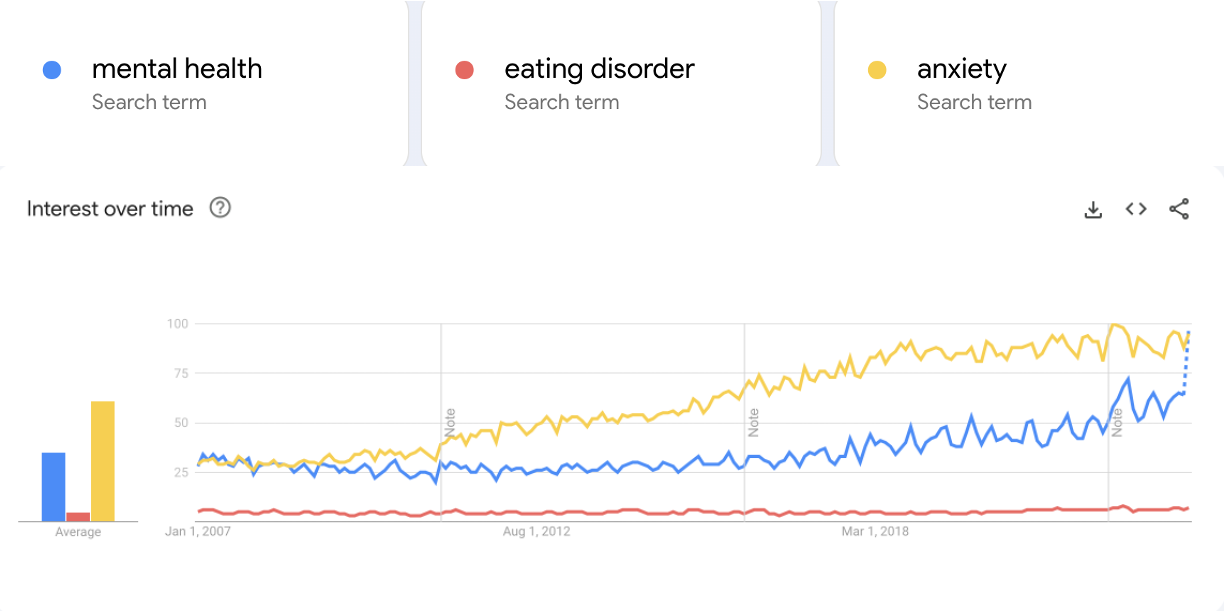

Despite the snowballing cultural pressure to be thin and the alarming rise in hospitalizations, “eating disorder” still has only a tiny fraction of the attention and interest that “mental health” and “anxiety” do.

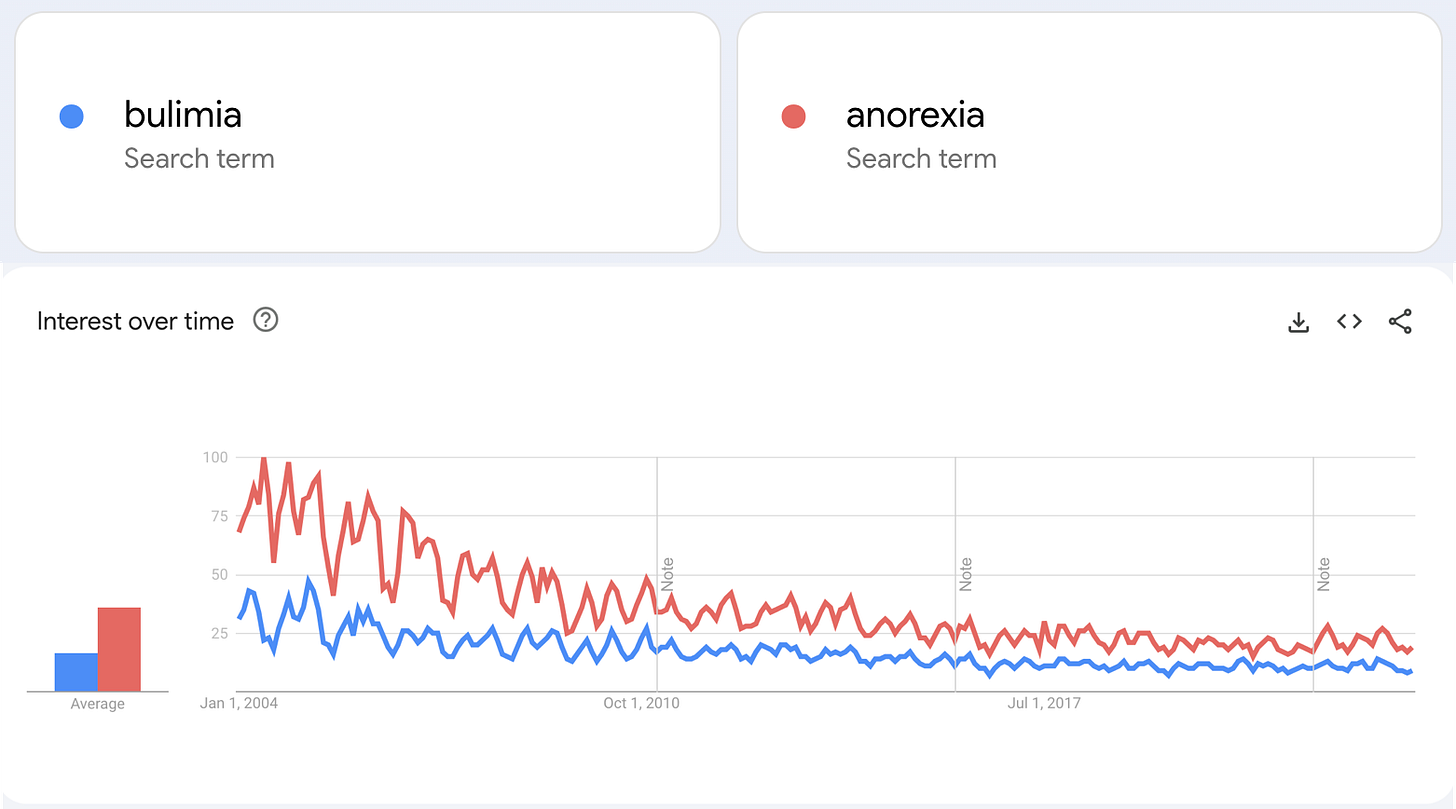

Meanwhile, search interest for “bulimia” and “anorexia,” the two most-well-known eating disorders that dominated Gen X’s adolescence in the “heroin chic” era and millennials’ coming of age in Tumblr era, has drastically fallen in the past 15 years.

Some of this may be a result of it going underground, or people using other search channels like TikTok and YouTube.

But now other, lesser-known disorders like orthorexia and binge eating are on the rise. We’re beginning to realize that maybe eating disorders are more complicated and multi-faceted than we thought… though there’s still a long way to go before they enter our everyday lexicon.

Society has made incredible progress candidly discussing and treating nuanced mental health disorders… but has not made the same progress with eating disorders.

They are clearly a much more insidious problem than we acknowledge… and continuing to ignore them is a very dangerous thing.

Second question:

Why are they so common?

To say the least, it’s complicated — but ultimately, it’s a struggle to take back some form of control… from an outer world with oppressive norms and elusive standards for how we should look and act, and an inner world where it’s hard to control how we feel.

“There is perverse pleasure in controlling our weight. Thinness is seen as a “relatively achievable” ideal in a time when we hunger for ideals.”

-The Cut

Ah, control. The dream of control, in a world we so inherently can’t.

It starts with achievement culture. The U.S. rewards discipline, performance and external outcomes, luring us to extreme behavior with the mirage of perfection.

“[My eating disorder comes from] pressure I put on myself. Lack of self-worth stemming from parents with high expectations who gave me positive attention via praise and acknowledgement of doing good things vs. just being who I am.”

-Anonymous

For women, the pressure to look perfectly thin is all the more real. Not only are they culturally valued by their looks, they are quite literally monetarily valued by their looks. Just ask the Economist.

Men, on the other hand, face a different kind of oppression — the need to go it alone.

“In high school I sort of envied the girls who did this openly… the camaraderie they had going to the bathroom. I was alone. In so many ways, it’s harder on women because men aren’t body-policed like women are. But I don’t think people take me seriously because I’m a man. It’s more pressure for women… but men don’t have a space to feel heard. “

-Anonymous

The pressure to meet these standards becomes all the more oppressive when you consider the problems with “ordered eating” in the first place.

First, the systemic problems — the ubiquity of sugar and processed foods, and unequal access to healthy, affordable food and nutritional education.

“Many, many people - Americans in particular - struggle with a culture which honors and rewards thinness, but aren’t given the tools to eat well. We create food deserts in low-income neighborhoods and then chastise those individuals for their unhealthy eating habits.”

-Anonymous

Second, portion size is out of control — yet we still feel a strange moral pressure to be part of the “clean plate club,” and very real, justified guilt when we let good food go to waste.

But even “typical” portions are a problem, because no diet is one-size-fits-all.

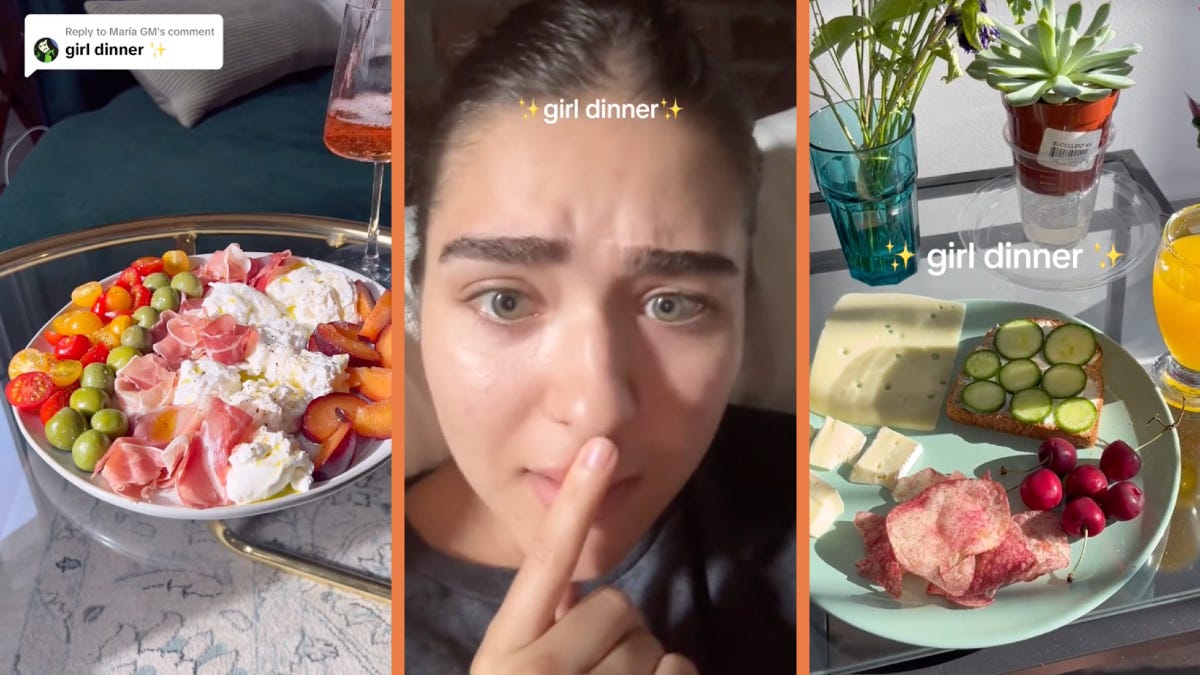

Consider the “girl dinner” phenomenon… and the ugly undertones it glosses over. It may seem like a funny, liberating movement for young women to embrace their weird eating tendencies… but it’s a symptom of a much more serious issue. The paradigm that we should eat three (predominantly meat-driven) meals a day is a relic of the patriarchy… the culinary equivalent of matching our AC settings to the male body temperature. Not everyone needs the same number of calories, or the same exact macronutritional intake. That means many women, smaller-framed people, and people with naturally lower metabolic rates have a difficult choice — either go along and allow themselves to gain weight, or quietly subvert the default eating expectation.

I’ve watched my mother and others in her generation cater to their husbands’ dietary needs for years, and many have confided that it would be easier to lose weight if they had the freedom to just cook for themselves. Meanwhile, many of my friends — myself included — have admitted to hiding eating habits from a partner… restricting their diet the moment they’re not around.

“Every relationship I’ve been in has been a challenge because I’m not always hungry on my partner’s schedule. I’m just not always hungry for breakfast, lunch AND dinner. I don’t want my partner to be looking out for things that aren’t there, but also things that are there.”

-Anonymous

It’s no wonder so many people resort to hacks, fasts, cleanses, and other “weird eating” tactics to maintain control.

The problem is, “weird eating” is a slippery slope to eating disorder.

They say marijuana is a gateway drug. That’s because it’s historically been the first thing people do once they’ve opened the gate. The moment you decide it’s okay to “break the rules,” you’re in uncharted territory… and now a whole world of options is at your disposal. You begin exploring things that the rest of the world doesn’t quite understand, and it’s easy to lose sight of what’s healthy for you and what’s dangerous.

To make it even more confusing, many of us learned these coping behaviors in our formative years… watching our parents model and justify “weird eating,” never calling it disordered.

“My mom refuses to identify her restrictive eating as an eating disorder. At some point when I was a kid, she survived only on Diet Coke and pretzels.”

-Anonymous

Now, perhaps due to the floodgates opening on the mental health conversation, many people are waking up to the fact that what they’ve battled their whole life is, in fact, a disorder.

”I’ve battled my disordered eating since early childhood, but until a few years ago, I never called it an "eating disorder. For a long time the only recognized eating disorders were anorexia and bulimia. Because I’m a binge eater, I felt like I didn’t fall into those categories because I didn’t purge nor did I restrict calories. I didn’t feel covered or recognized by the ED community until binge eating disorder was more widely recognized.”

-Anonymous

“I finally bit the bullet and told my psychiatrist about my fasting and binge eating. I felt like a huge weight had been lifted. I’d been okay with calling my depression “depression” for over a decade, but it took me forever to come around to this as a disorder, too. I’d always thought of eating disorders as this extreme thing… like you had to be severely malnourished to seek treatment. It was liberating to realize that it was okay to ask for help.”

-Anonymous

But even still, this is a hard realization to voice openly… because unlike other mental health issues, eating and fitness have a deep-seated, stubborn moral component.

Gluttony and pride are two of the “seven deadly sins” deeply rooted in American culture. So it’s no wonder people internalize their struggle with EDs are their own fault, not faulty wiring:

“It’s not just the way my brain is wired, it’s something I’m doing to myself. It’s easier to own up to things that are chemically there — but with this, there are other reasons, like vanity.”

-Anonymous

Third question:

Where do we go from here?

Given the choice, I will always choose optimism. And when it comes to eating disorders, there are a few very real signs that do give me hope.

First, the progress we’ve made normalizing mental health struggles and neurodivergence has paved the way for more open dialogue about eating disorders — as long as we don’t glorify them for their divergence or their extremity, and view them for what they really are:

“Neurodivergent TikTok has been helpful because it’s created an open dialogue, but it’s also dangerous because a lot of people (especially Gen Z) seem to glorify being divergent because it’s ‘special’ and ‘interesting.’ But there’s nothing interesting or cool about having an eating disorder. It’s smoothing over the tough parts. It’s not all fun and games.”

-Anonymous

Discussing eating disorders in the open will require us to be a bit braver, more vulnerable, less judgmental and more understanding of each other:

“The thing that's hard is this isn’t about body image or being skinny. That's one piece of it. But this is about feeling worthy. And that's something we all struggle with - so I wish we could talk about these things more safely. We all have our coping mechanisms - why does mine have to be so hush-hush and tabooed? Why is an eating disorder worse than drugs or alcohol or whatever?”

-Anonymous

Second, while it may be controversial, I do believe that Ozempic and its ilk are a net benefit to an overly obese society in which far more people than we realize struggle with their relationship to food. These new drugs are changing the way we think about eating — from a sheer act of will power to a result of our genetics and brain function, not entirely in our control.

“A healthy body can generally signal to the brain when it has had enough food. But that signalling system can be faulty, or get injured …. If we get past [Ozempic] as a celebrity-weight-loss headline story, and we see this for what it really is, it’s revolutionary. In the future it might be like taking vitamins.”

-Jia Tolentino for the New Yorker

Right now, it’s hard to separate the conversation from the persistent class conflict that permeates many other aspects of our society. Ozempic and Wegovy are expensive — incredibly expensive — and it’s frustrating to see rich people use them as a “cheat” to get thin quick, rather than these drugs genuinely helping the lower- and middle-income people who struggle to afford healthy food in the first place.

Plus, there’s the question of side effects. Aside from the long list diabetes patients might face (outlined in this objectively ridiculous Ozempic commercial), there’s also the case of “Ozempic face”, mental health effects, and who knows what other horrors might arise in the future.

As with all treatments, though, it’s a question of risk tolerance — and for many who’ve struggled all their lives to lose weight in a system that judges them, stacks the odds against them, and forces them to battle eating disorders in secret… the benefits of pharmacological intervention might far outweigh any side effects.

The New York times made waves last year reporting that anorexia doesn’t always look like what we think it does. Far more people are starving themselves than we realize… people of all shapes and sizes, in anguish, suffering in silence.

Maybe those people are your family or friends.

Maybe they’re even you.

So I suppose I’ll end with one last, final question…

Isn’t it better to ask?

If you or someone you know is struggling with an eating disorder, consider consulting the National Alliance for Eating Disorders’ free support line.

Please also consider funding NAED and other organizations like it, advocating to de-stigmatize eating disorders, and, if you’re up for it, even innovating new support systems for the millions of Americans who struggle.

”All these wellness companies building the future of retail health, where are you [on eating disorders]? With my capitalist hat on, there is a market here. And I think it could actually really help people.”

-Anonymous